The power of putting yourself in the picture

These days we think nothing of holding our smartphones at arms’ length, tilting our heads to find the perfect angle and snapping a selfie. Billions of self portraits, billions of moments captured by digital technology flooding social media platforms every day, glimpses of our lives that we choose to share with the world.

It’s a far cry from the origins of the self portrait, back in the mists of the 15th century when painter Jan van Eyck unveiled his Portrait of a Man in 1433. Historians have debated (and will continue to do so) whether this was the very first self portrait, but for the purposes of this blog, it’s a good place to start.

I’m going to explore the power of the self portrait and self portraiture, examine its evolution from the early days of the Renaissance to the modern phenomenon of the selfie, what it means to the artist and explore how this singular form of painting and photography has turned storytelling into the most exquisite art.

Why are self portraits so important?

As I mentioned earlier, we can trace the birth of portraiture and the self portrait to the early Renaissance and the 15th century, when painters and artists turned their gaze from external subjects to themselves, presenting them to the public viewer for scrutiny.

Some historians connect the origins of self portraits with the revival of the linear perspective in art, as well as technological developments that led to the manufacture of mirrors that offered a clear reflection – putting artists in focus – for the first time.

Imagine the thrill of being able to see your features clearly: every detail of your skin, hair and features shown in sharp relief. How could artists who had made careers from capturing the likenesses of other people not be inspired to grab their brushes, put paint to canvas and create their own self portraits?

Albrecht Dürer is one of the best examples of how early self portraits quickly evolved. At the tender age of 13, the artist created self portraits using silverpoint, following it up over the years with versions in pen and dark brown ink, oil on parchment, and oil on panel.

While earlier self portraits were quarter views of his face, as if he were painting himself while looking from the corner of his eye, Dürer’s startling 1500 self portrait, depicting him as Christ (echoing Leonardo Da Vinci’s

Salvator Mundi, painted around the same time), looks you dead in the eye. It bewitches art lovers to this day.

From Dürer's Christ self portrait to Rembrandt's visual diary

As well as this confrontational style of self portraiture, one of the biggest changes to take place during and after Dürer was the shift in perception of artists and painters. Before the Renaissance, they were lumped in with all other craftsmen – their elevation to something quite different, and in some cases very special, had not yet begun.

One of those who achieved greatness was Dutch artist Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn – better known as Rembrandt. After opening his own studio in around 1624 at the tender age of 18 and forging important connections such as statesman Constantijn Huygens, Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam in 1631 and made a name for himself as a professional portraitist.

In the years that followed, he created an astonishing body of portraits and self-portraits, many of which bore his trademark use of light and shadow, separated by the subject’s or the artist’s nose (depending on who was sitting). The 1637 canvas A Polish Nobleman is a striking example, and it’s a technique repeated again and again in Rembrandt’s almost 100 self-portraits.

A life in paintings

This 40-year, incredible visual feast chronicles his life as an artist and painter, from being a dapper young man, through to the powerful, unflinching canvases of his later years, complete with craggy features and glowering stare. Intriguingly, each self portrait was created with the use of a mirror, so the viewer is actually seeing the subject in reverse.

Historian Kenneth Clark wrote that Rembrandt was “with the possible exception of Van Gogh, the only artist who has made the self portrait a major means of artistic self-expression, and he is absolutely the one who has turned self portraiture into an autobiography.”

Vincent van Gogh, self portraits and the art of performance

Rembrandt wasn’t the only artist creating a buzz with self portraits, but he was among several who used their paintings to tell his own story.

For example, there’s a world of difference between the 1628 portrait Rembrandt Laughing, the 1639 Self Portrait with an Architectural Background (currently held by the Paris Louvre) and the enigmatic Self Portrait with Two Circles, created between 1665 and 1669.

They reveal a man who has not merely faced the slings and arrows of life, but documented them in images that can be unsettling and prompt uncomfortable questions about oneself and the world.

Arguably the most famous painter to put their life – and mental and emotional pain – on canvas is Vincent van Gogh, but he also painted portraits throughout his career, and wrote that they were: “the only thing in painting that moves me deeply and that gives me a sense of the infinite”.

As an impressionist, van Gogh constantly tried to depict his own feelings about and involvement with his subjects in each image, trying to reveal the inner qualities of the figure in the painting. “It’s difficult to know oneself – but it’s not easy to paint oneself either,” van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo.

Depicting pain in oil and canvas

Like Rembrandt, van Gogh used mirrors for each self portrait, painting his own face and head, again and again from around 1886 to 1889. Self-Portrait with Dark Felt Hat, believed to be one of van Gogh’s earliest self-portraits, dating from 1886, is dark and gloomy, and at first glance seems to offer precious little insight into the artist.

However, history tells us he was in poor health at the time the self-portrait was painted, and that shock of red beard at the centre of the self portrait hides the fact his teeth were falling out. Van Gogh’s sombre, grey city clothes try to persuade the viewer he’s from a middle-class background and he’s conventional, someone they can trust to paint their image, their story. It’s a performance.

Vincent van Gogh’s later self portraits bring his extraordinary face into the light: they are paintings peppered with bursts of sunshine yellow from straw hats or an easel or his beard, before Van Gogh turns to the cool green and blue hues that dominate the final three self-portraits created in Saint-Rémy, in the months before van Gogh died.

Just two of van Gogh’s self portraits feature the artist’s infamously wounded ear (Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear was the centrepiece of a Courtaulds’ exhibition this summer). Both were painted in 1889, and both are striking in their emotional resonance. They’re over a century old and yet remain utterly contemporary in their beauty and their boldness.

What does a self portrait portray to the viewer?

While Vincent van Gogh used his paintings and self portraits to capture something of his internal, mental struggles with, Mexican painter Frida Kahlo created works that, in no uncertain terms, told gallery and museum visitors the story of the chronic pain she endured during her short life.

As a youngster, Frida was creative and enjoyed art. She was inspired by Mexican nature and artifacts, but she never considered painting as a career. All that changed after she was badly injured in a bus accident in 1925 when she was 18.

She was impaled by a metal handrail “the way a sword pierces a bull” and suffered terrible injuries, including three displaced vertebrae. Frida was confined to bed for around three months, and it was during this time she took up painting, using a special easel and our old friend the mirror placed above it, so she could see and paint her face.

Exploring oneself in a self portrait

She said: “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best.” Her paintings drew on a range of inspirations, from Botticelli to cubism, and increasingly Mexican folk art as she depicted images that combined beauty and ugliness, pain and death.

Like Vincent van Gogh, Frida Kahlo’s self portraits reveal something more profound about their creator. Her series of medical paintings feature Kahlo bleeding and her open wounds on full display, a constant reminder to the viewer of the pain and hurt she was living. Her frequent depictions of La Llorona and La Malinche, two central female figures from Mexican folklore, also allude to calamity or misfortune.

Her 1932 painting Henry Ford Hospital, in which Kahlo’s self portrait depicts herself lying naked and bleeding on a hospital bed, while her messy hair and exposed heart echo child-murderer La Llorona. Over the years, the art work has come to represent the Mexican taboo of women who choose not to have children – a surprising and profound tale that went beyond Frida’s own melancholy over her failed pregnancies.

Self portraits and photography

Like so many artists, Frida Kahlo found greater fame after her death than when she was alive. Tate Modern dubbed her “one of the most significant artists of the 20th century”, while Van Gogh’s mystique as a painter who suffered for his art, only to die a young man, took off in the last months of his life and grew to his becoming an icon of the art world.

In 1998, a self-portrait by Vincent Van Gogh was sold for an astounding $71.5 million, 10 years after another self portrait went under the hammer for $24 million. Portraiture and self portraiture, as had been the case for centuries, was the preserve of the wealthy.

The closest ordinary people got to this form of art was to visit their local art gallery or museum, or take a trip to London or Paris to peer from a discreet distance at the greatest, most creative portraits and paintings. Photography changed all that.

The dawn of a new era for self portraits and portraiture

We have Robert Cornelius, an amateur chemist and photography enthusiast from Philadelphia, to thank for what is regarded as the world’s first selfie, writing on the back of the photo: “The first light Picture ever taken. 1839.”

It was the same year Louis Daguerre introduced the photographic process and it didn’t take long for portrait studios to begin popping up in major cities. The general public was wary of this new technology, prompting photographers to turn to 19th century celebrities, such as Charles Dickens and Abraham Lincoln, and use their self portraits, publicise the medium.

It didn’t take long for photography to catch on as a national pastime. In America, they used it to record history, capturing the visit to Washington CD of 90 Native American delegates, while in 1870, the Allan Pinkerton National Detective Agency took a self portrait of a criminal – launching what would become the world’s biggest collection of mugshots.

In the UK, photographs captured a self portrait of Queen Victoria and her family in the 1840s and, 20 years later, she allowed photos by London-based snapper John Mayall to be published.

Photography and the self portrait going global

Photography really took off in 1888, with the sale of the Kodak No. 1 camera. Suddenly the creative pastimes of portraiture and self portrait were in the hands of the masses, and the art form was democratised like never before.

It gave rise to extraordinary talents, including the hugely influential conceptual artist Cindy Sherman, prolific photographer Robert Frank, Dutch wildlife photographer Frans Lanting, portrait and fashion snapper Richard Avedon, and prolific celebrity portraitist Annie Leibowitz.

Spool forward around a century and we come to the first-ever cameraphone, the Kyocera Visual Phone VP-210, released in Japan in 1999. Dubbed a “mobile videophone” it boasted a 110,000-pixel front-facing camera.

The age of the smartphone and the selfie

The year 2000 saw the release of the Samsung SCH-V200, and Sharp Electronics J-SH04 J-Phone, both regarded as the first digital smartphones, but it was the launch of Apple’s first iPhone in 2007 that sparked the selfie revolution.

It turned anyone who could point and click a smartphone into a photographer, while the rise of social media platforms provided the ultimate global art gallery with millions of self portrait images published: a melting pot of ideas and inspiration.

Subsequent generations of smartphones have seen vast improvements to their camera technology, allowing you, me and everyone else to capture our selves in increasingly minute detail, to tell our stories on a local, national and global level.

Truth and the self portrait

A great example of an arresting image is my Self Portrait as Harlequin, which allowed me to explore my love of dance and movement. The colourful, playful figure at the centre of the art work, with his golden mask and crown, is practically extending an invitation to join him on that chequered floor.

Likewise Golden Boy and Monochrome Me are explorations of my face. They both feature a direct, present figure and act almost as a form of mirror. Self portraiture has always been an exploration of oneself, but the answers I find may be completely different to the viewers’ interpretation.

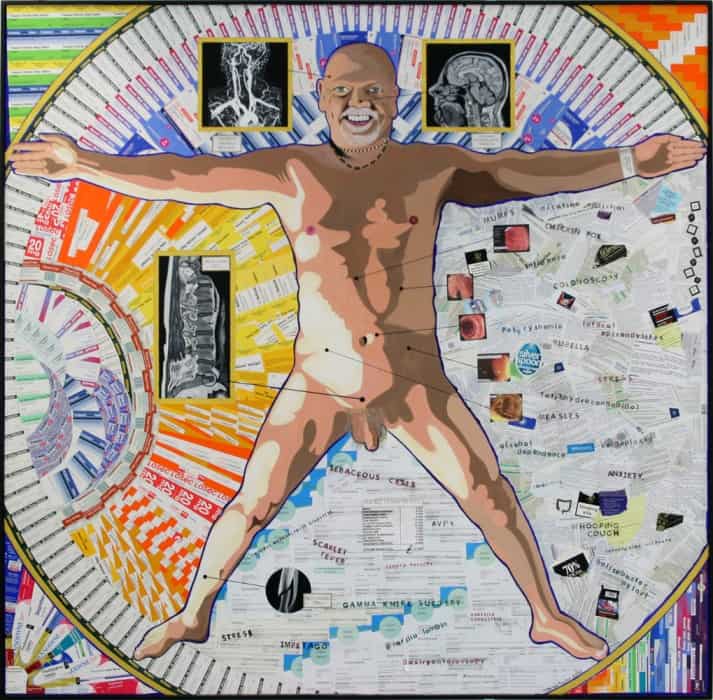

There’s no disguising the inspiration for Alive & Well, and while it depicts me in a similar position to Leonardo da Vinci’s work of art Virtruvian Man (currently held by Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia) that’s where the similarity begins and ends.

Alive & Well is a potted history of my physical health, the background of the painting is made up of medical bills and info leaflets, pill packets of all the drugs I’ve taken, as well as scans and X-rays. I wanted it to be more than just a likeness, more than simply holding up a mirror to myself.

I wanted this life-size artwork to present me as fighting fit, and while I’ve faced my fair share of ups and downs, the inspirational juices are still flowing, a feeling that’s almost impossible to capture in a simple selfie.

As an artist, I think there will always be an appetite for portraits and self portraits, even in the current era of instant gratification provided by the selfie. People yearn for connection, for experience, for insight.

From Van Gogh’s haunted expression, a self portrait captured from the reflection in a mirror, to Annie Leibowitz’ iconic Vanity Fair cover photo of Caitlyn Jenner, self portraits have turned making “windows into men’s souls”, to quote Queen Elizabeth I, into a timeless art form. How could I not be tempted to pick up my brushes and create?

What is the message of self-portrait?

The democratisation of the self portrait on social media platforms has, unfortunately, exposed people publishing their selfies to the opinions of the wider world, even if they are posting among friends.

It’s a consequence we artists are all-too aware of when we put flesh on the bones of our ideas and beliefs and take part in a local or national exhibition. We critique the art of those who came before us and our peers, whose works hang in a gallery or museum, whether they’re in London or Lesotho, Paris or Pune.

The act of putting your face in the centre of an image is an invitation to examination, both of the subject and oneself. But the fleeting nature of social media and our increasing desire to consume, to move on to the next thing, sometimes what’s behind the selfie gets lost.

The smartphone has replaced the medieval mirror, our thumb the painter’s brush. A life, a head, can be snapped in a moment, and is sent out to jostle among the vast number of portraits featured on every platform.

What are we trying to say with all these selfies? What are we trying to tell our audience? Are we simply seeking validation? The message behind self portraits is one that takes us all the way back to 1433 and Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man: look at me.

The act of looking – whether you’re browsing a gallery or museum, or scrolling your news feed – makes the viewer stop what they’re doing and give an artist their attention. That’s the real art.