David Hockney famously quipped: “I’m a very early riser, and I don’t like to miss that beautiful early morning light”. Every artist, no matter their milieu, understands that light is one of their most important collaborators. Even an absence of light will be used to further an idea or create a project.

As Hockney suggests, light is elusive and quixotic, no two moments are the same and the art of creation lies in capturing the particular way something or someone looks at an exact point in time. It can be at the same time both terribly frustrating and immensely fulfilling.

I use light in different ways in my work. Sometimes it’s to illuminate, other times it’s to draw the viewer into a place or scene. No matter what I’m capturing on canvas, light is often a hugely important component of each piece.

As you might expect, my landscape collection features lots of bright, blue skyscapes, but in The Block, the spotlights crossing in front of the colourful balconies alter the shades, but also make you wonder what is going on just out of your eyeshot.

Meanwhile, Cinque Terre – Venazza, one of a series of picturesque Italian fishing villages, has an almost hypnotic quality as the light plays on the water, while there’s a subtle separation among the surrounding buildings. Those in the sun’s rays feel warmer, while those in the shadows are slightly less welcoming.

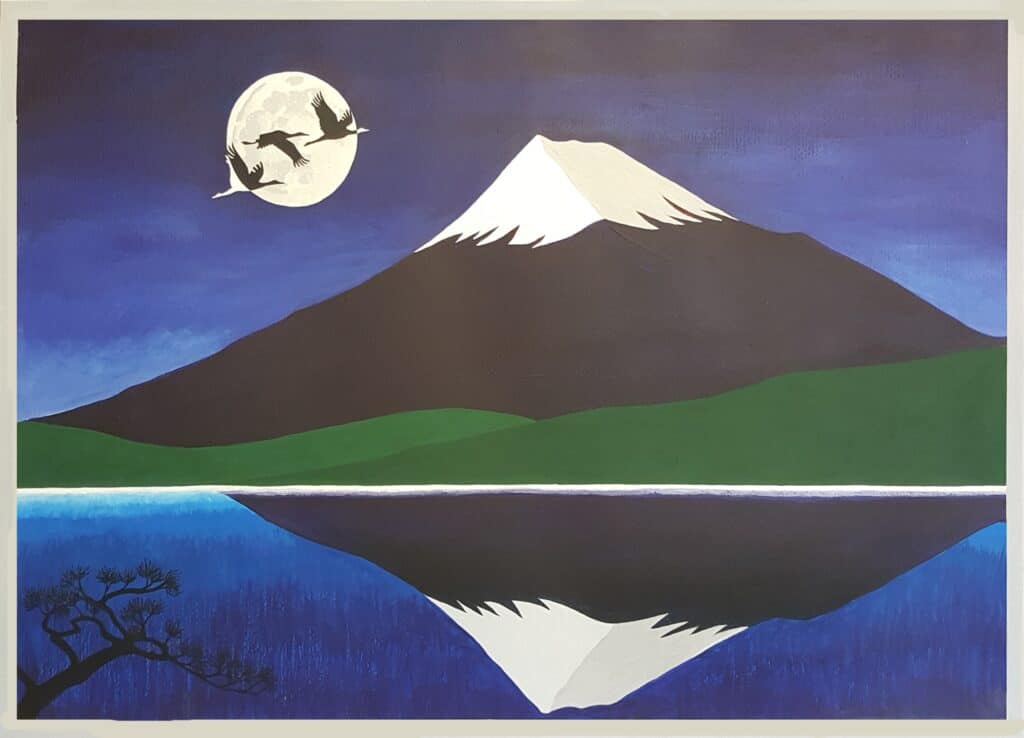

Then there’s Fujisan by Moonlight, which plays around with reflections and light when there is little to be had. It’s both evocative and illusory, and a good example of how light – and its absence – can be used to draw in a viewer.

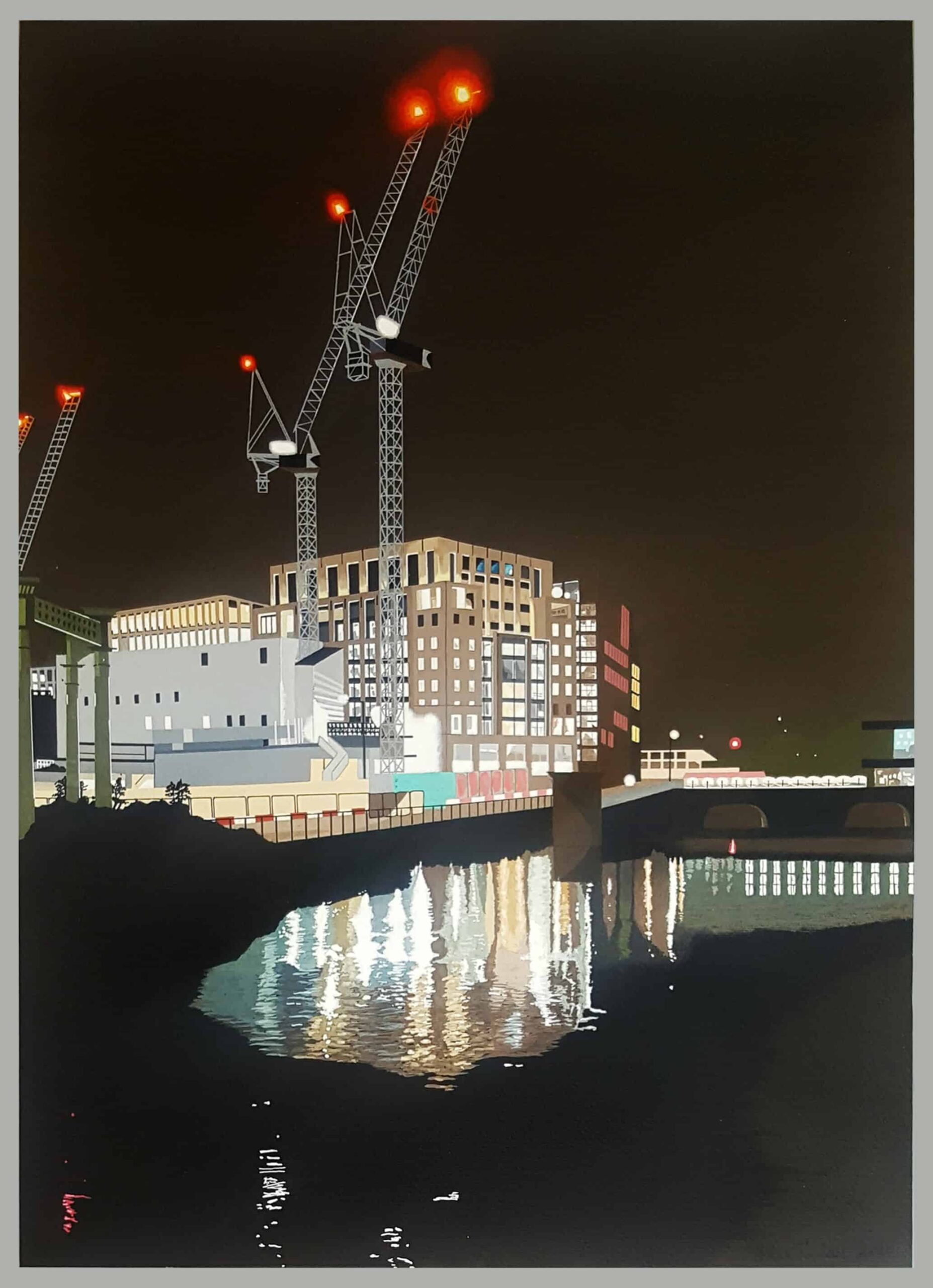

When it comes to finding the best light, it changes from artist to artist and painting to painting. The broad swathes of artificial light that reach into every nook and cranny are perfect for pieces such as Lockdown, while Light into the Dark demonstrates how concentrating incandescent, electric light into the centre of a piece can be both startling and absorbing.

You can take electric light in all directions imaginable, from using it to illuminate a space, form shadows or – like Pablo Picasso – entire images, as per his stunning light photos from 1949, which used a small electric bulb in a dark room and ended up in Life magazine.

We have the quick-thinking photographer Gjon Mili to thank for those superb pieces, after a 15-minute session with the notoriously prickly artist turned into five full meetings.

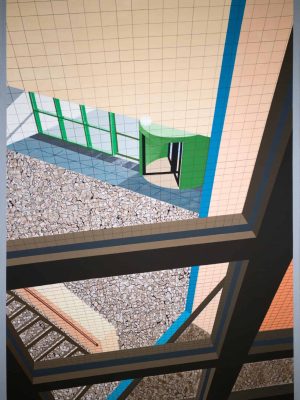

Natural light through windows can also be – pardon the pun – illuminating, enabling artists to play around with texture and, in the case of The Clore Gallery – Tate Britain #5, shadow and perspective too.

The trick with light is to look and look and look again – as Hockney said: “Drawing makes you see things clearer, and clearer and clearer still, until your eyes ache.” Find what works for you, from the high, clear skies of coastal light to the swirling grey of a brooding mountainside, and let your innate creativity take care of the rest.