Inspiration. It’s the start of all creativity, the fuel that drives the art world and everyone in it – including me. But the things and images that prompt us to pick up a brush or a pen or a chisel can vary wildly.

I’m an acute observer of what’s going on around me, and my ability to notice everything going on means I can take inspiration from almost anything. My art is to then turn what I see into my vision of the world and share its beauty with my audience.

In this blog, I’m going to focus on my love of architectural art, why architecture features in art, explore some of my favourite pieces and profile some of the world’s most iconic architects.

How does architecture become an art?

Perhaps it’s my scientific background, but to me architecture has always been about far more than piling bricks on top of each other to make a whole structure.

It’s also a complex and awe inspiring blend of art and science: curving, precipitous walls, the magic of glass, linear compositions where natural light and shade combine in endlessly fascinating ways. They are temples of inspiration!

It may surprise some readers, but there is a long-running argument about where the line is drawn between architecture and art, and if they are actually two separate and distinct things.

One side insists the medium simply has to be an art as it’s a form of self-expression, while others disagree passionately.

I’m firmly in the former camp and, as someone who is acutely observant, I can find even the smallest of details in an architectural subject enticing.

The world is my art gallery

The sheer number of colours crammed into one doorway is what initially catches the eye in ‘Old & Tired’, but look closer, and you soon see the architectural features surrounding it also have something to say. They hint at a more elegant age, when it wasn’t waiting for an eagle-eyed artist to put it firmly in the spotlight.

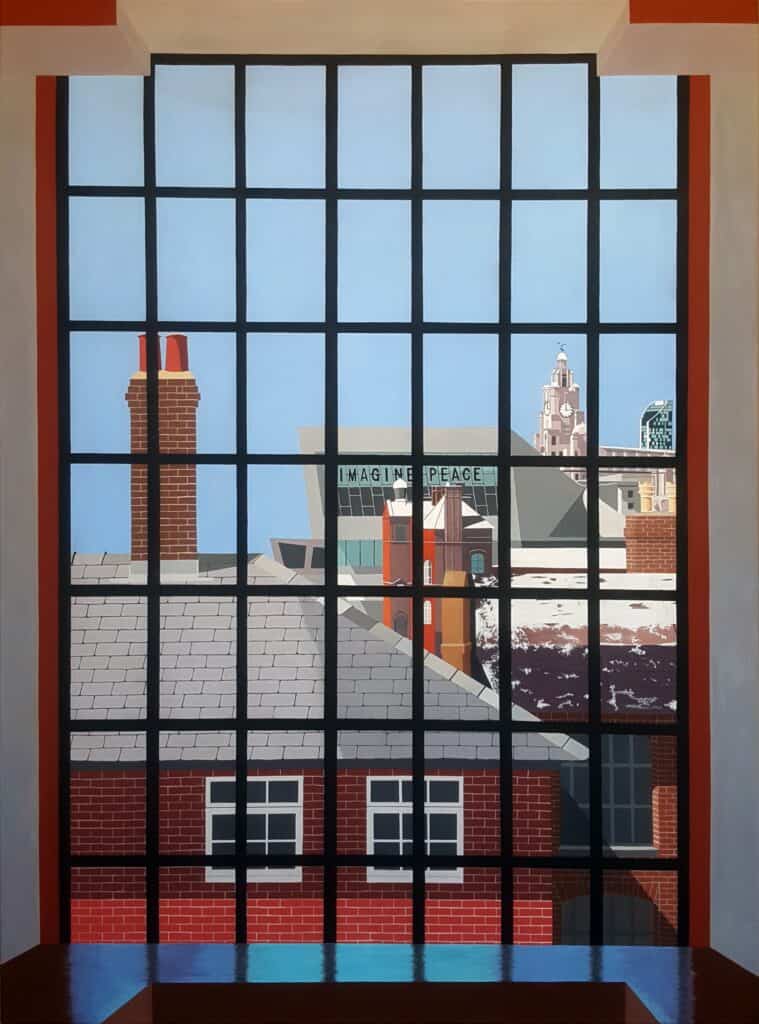

I use architecture both as a frame and a subject in my painting ‘The View’ from Tate Liverpool.

The huge window becomes a springboard to the built environment beyond, which is filled with evocative buildings, from the relatively drab brick house to the beautiful and rather more aesthetically pleasing Liver Building, one of the finest in the city.

Both lead us to a very important question…

Is architecture considered an art form?

The primary function of architecture isn’t to be an artwork. Buildings are designed for a purpose: to be lived or worked in, they house machinery and materials. By their nature they are created to be practical.

But that doesn’t mean they can’t be beautiful or have an artistic purpose that extends beyond what they contain. Think of Stonehenge, Europe’s great medieval churches, or Santiago Calatrava’s breathtaking City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, an icon of contemporary architecture.

It doesn’t have to be on such an epic scale either. I see interest and inspiration in places that perhaps other people don’t: from the geometric splendour of Hong Kong Memories to the magnificent light I captured in Airports of the World – Malaga.

In creating a building, architects are not just designing a space for an office or shop or art gallery. They are bringing to life an idea in its own right: one that will occupy a public space in the urban landscape and – hopefully – start a conversation about the creative process and architectural form.

Not every building that’s ever been suggested has been a success. A proposed extension to the National Gallery was junked after Prince Charles dubbed it a “monstrous carbuncle”.

But there are plenty of examples that have inspired generations. Let’s take a closer look at some standout creations and the architects behind them.

Frank Gehry

Think of this American architect (who was also great at furniture design) and Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles might spring to mind.

Gehry created sinuous, modernist architecture that resemble sculptures more than buildings. His Fish Sculpture for Barcelona, host city of the 1992 summer Olympics is a perfect example and while it looks outlandish, it’s an astonishing feat of engineering brilliance.

While his buildings feature a swirling aesthetic, as he moved from architecture to artist throughout his career, other pieces, such as lamps and sculpture, featured strong fish motifs as he tapped into the natural elements that inspired him for years.

Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, better known as Swiss-French genius Le Corbusier, is regarded as one of the pioneers of modern architecture, and used urban planning to create better living conditions for people in overcrowded cities.

Le Corbusier also tried to standardise modern architecture under an ‘Esprit Nouveau’. It was an arresting form of visual art that notably saw several of his buildings elevated on stilts.

It gave them an incredible delicacy and grace. Unlike Frank Gehry, who liked to create curving forms that looked more like sculptures, the point of Le Corbusier’s purist style was crisp, clean lines, underscored by horizontal bands of windows and an external space dominated by a lush, green environment.

There are elements of Le Corbusier’s style in my paintings Rhapsodic and Beach Shelter, which echo his linear architecture and practice of putting buildings on stilts.

Frank Lloyd Wright

When it comes to the fusion of architecture and art, few do it better than Frank Lloyd Wright, the man behind the American architectural Prairie School Movement.

Arguably most famous for the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, as well as the beautiful private home Fallingwater, in Pennsylvania, architect Lloyd Wright was responsible for more than 1,000 buildings over a 70-year career that continues to influence architectural design – and art – to this day.

His ‘prairie-style’ and Usonian houses were not dissimilar to Le Corbusier, though they were created decades before – featuring low-slung bands of brick or concrete, broken up by horizontal windows.

While I’m fascinated by the buildings, what makes architect Lloyd Wright really stand out for me are his exceptional skills as a contemporary artist. His geometric compositions are great examples, and there are echoes of his intersectional style in my painting Bubble & Squeak #4.

Zaha Hadid

Lloyd Wright wasn’t the only great architect who used art as a means of expression. Zaha Hadid considered herself an artist above everything else, even when she became a fully fledged architect.

The importance of being able to set out her artistic vision was fundamental to being able to create the three-dimensional architectural forms Hadid wanted.

Her astonishing contemporary art led to some of the most beautiful and artistic buildings in the world, such as Azerbaijan’s sinuous Heydar Aliyev Centre.

How does the art world link with modernist architecture?

It’s a good question. For me, the two are inseparable and the connection isn’t just with modernism; it goes all the way back to cave paintings.

As I wrote earlier, architecture has a purpose, a function, and no matter how sterile the design of the building, there will always be someone who thinks it is beautiful or has artistic merit.

Think of the Brutalist style that cropped up across the country during the 1950s. It was functional, almost severe, prioritising structural elements and minimal materials over design or sculpture.

In the context of its function, it was perfect: Brutalist architecture projected a sense of robustness, solidity, three dimensionality.

It got a pounding from artists and critics for exactly the same reasons: the lack of visible artistic flourish meant these buildings didn’t so much occupy public spaces as brood over them.

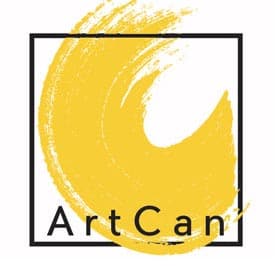

There’s a hint of that in my painting Light into the Dark, which is dominated by the great architectural monolith of a building on the Regents’ Canal development at Granary Wharf.

Yet some of these buildings have become as cherished as a perfectly preserved Roman building or a magnificent stately home. Why? Because tastes change. We move on from history.

As new generations reinvent the culture around them, what was once deemed ugly or out of fashion is suddenly the architect and art communities’ hottest commodity.

The eco-architectural revolution

Green architecture is one of the best current examples. It’s become the pet project of almost every architect and incorporates sustainable or environmentally friendly materials in the development of buildings.

Think solar panels, organic roofs, thermally efficient heating and cooling systems – and natural materials such as wood and glass that bring a creative element to a space, while also blending form and function.

Given his love of nature, I think Frank Gehry would have been delighted to see green design in the work of modern architects.

What is the art period of architecture?

The connections between art and architecture go way back into history, and in some cases it’s difficult to see where one form influenced the other.

Architects and artists have been inspiring each other for centuries, with Asian, Middle East and African influences permeating western culture and architecture and vice versa.

Arts sculptures standing proud in an open space have enhanced all manner of classical buildings. What stately home doesn’t have art of all kinds hanging from its walls, and can you imagine the Sistine Chapel without that breathtaking ceiling?

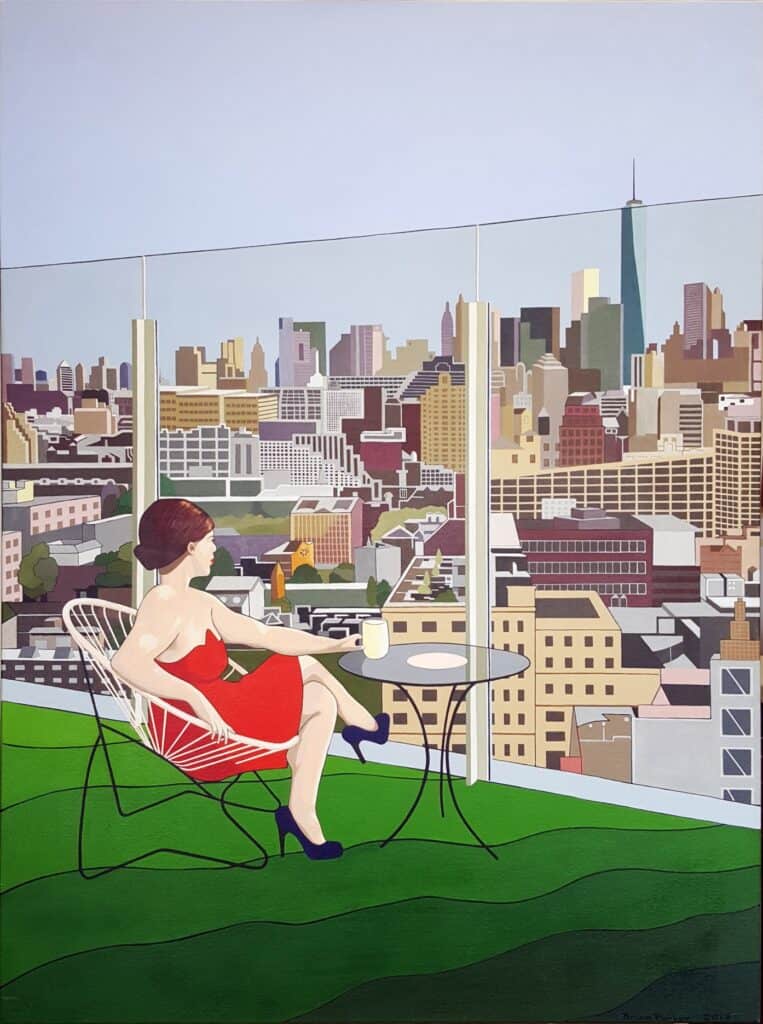

Likewise in paintings, artists have been inspired to capture buildings either as a backdrop to or a setting for an instant of high drama – think of all those religious paintings packed with classical architecture such as colonnades – or a more still moment, such as my painting Manhattan Skyline.

It draws your eye from my friend Brittany out to the buildings arranged before her, making you wonder who is behind all those windows..?

At the same time, architecture in art serves as more than a stage: it’s also a window into history, allowing us to remember how things once were. I’m thinking of William Hogarth’s images of a dissipated society and Stephanie DEES’ haunting, cheek-by-jowl Scottish tenements.

Architects can use templates provided by artists as a way to improve our present built environment, creating a new art form in the urban sprawl.

Art and architecture: forever joined

I don’t think it’s possible to have architecture and art as two separate and distinct beasts.

For me, buildings and their surroundings are a fundamental source of fascination, allowing me to create interesting paintings that stimulate the visual sense.

No matter what they are used for, buildings, like artworks, are subjective and that’s perhaps their real point, their true function.

Whether it’s to create a home for a magnificent sculpture, or to provide a blank canvas for all manner of artists, architecture can be a springboard, a delivery device for any artist looking to take their first steps, expand their creative process or give an old hand a new project to focus on.

One thing’s for sure: I’m going to be adding to my landscapes category for quite some time to come.